In our last post, we talked about what 3D reconstruction is and why RoadBotics is pursuing this technology. Now, let’s dive a little deeper into how we create a 3D reconstruction.

Given a real-world scene like a parking lot or all of the sidewalks for a city, how can we create a digital copy of it?

Understanding the world in 3D has been an open problem in the field of computer vision for several decades, inspiring the creation of many methods for computers to capture 3D structure. Most methods fall into one of four categories: structured light, LiDAR, deep neural networks, and SLAM.

Before we get to how each method works, one thing to note is that although the goal is to create a digital representation of objects using surfaces and textures, 3D reconstruction begins with a collection of 3D points in space, known as 3D point clouds. Each of the methods below provides a different way to capture a 3D point cloud of a scene.

Basics of the Different Methods

Now let’s talk about how each method works.

Structured Light

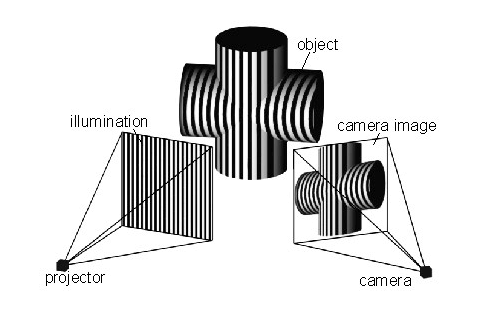

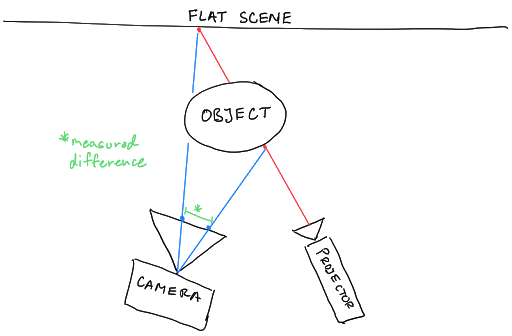

Making a 3D reconstruction using structured light usually requires two pieces of equipment: a projector and a camera. The projector projects a pattern of dots onto the scene to reconstruct, and the camera takes a picture of the scene with those overlaid dots.

A computer then measures the distance in pixels between each dot in the captured image and where the dot would be if the scene was a flat surface. Using these distances, the computer can calculate the real-world depth of each dot in the scene, creating a depth map that can be easily converted into a point cloud. This is the basis for Microsoft Kinect (version 1) and Apple’s FaceID.

LiDAR

LiDAR stands for light detection and ranging. It is a technology heavily used by autonomous vehicle companies to enable their cars to capture a 3D view of the world around them in real time.

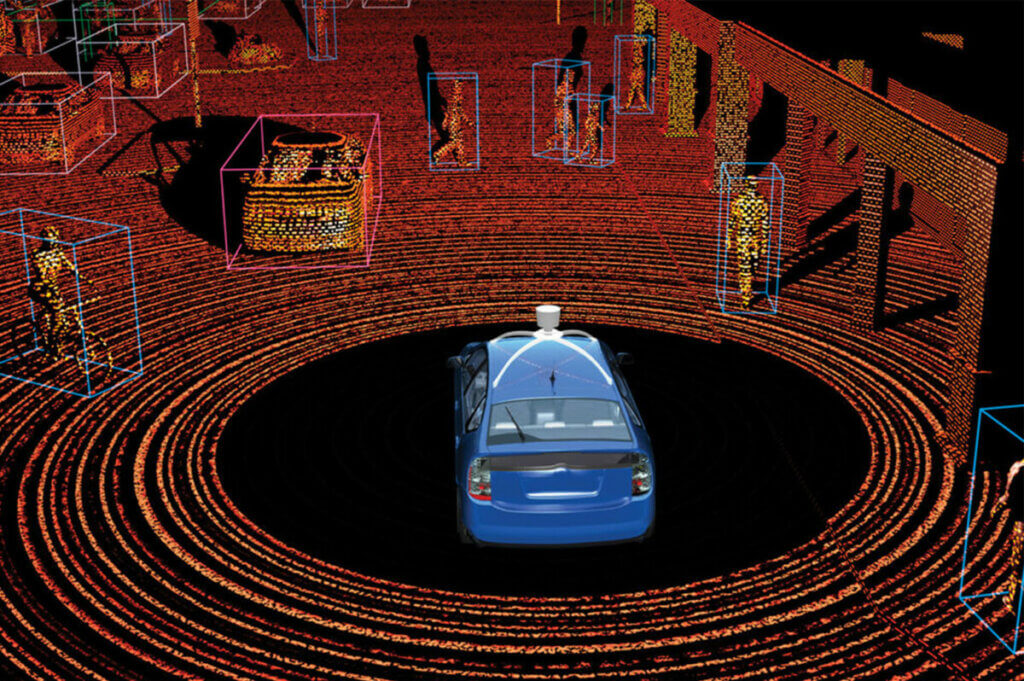

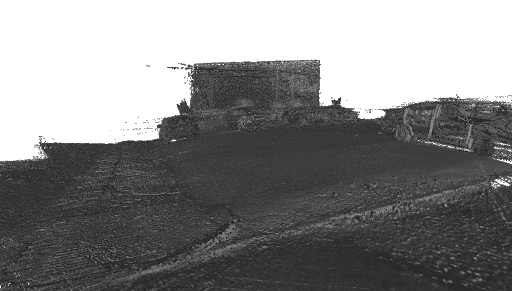

Like structured light, it also requires specialized equipment: in this case, a LiDAR scanner, which is a combination of a synchronized laser and camera. The LiDAR scanner works by flashing the laser to illuminate a single point in the scene and then measuring the time it takes for the light from the laser to bounce off an object and return to the camera. This measurement is generally called time-of-flight and, using the known constant for the speed of light, can be used to calculate the distance from the LiDAR scanner to the illuminated object. This is then repeated for many points across the whole scene to build up a 3D point cloud. In the image above, you can see an example of a LiDAR point cloud. The points are arranged in concentric rings created by and centered on a rotating LiDAR scanner mounted to the top of the blue Prius. In the gif to the left, you can see an animation of how one of those ring-of-points is created.

Photo Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lidar#/media/File:LIDAR-scanned-SICK-LMS-animation.gif

Deep Neural Networks

Deep neural networks (DNNs) are the newest set of methods for performing 3D reconstructions. While structured light and LiDAR methods rely heavily on specialized sensors to capture 3D data, DNNs usually only require a 2D image or pair of 2D images as input. Using sophisticated pattern recognition to estimate the position of objects, a DNN can generate the 3D structure of the scene. This often takes the form of a DNN which takes in an image and produces a depth map.

It should be noted that such a DNN is a machine learning algorithm. This means it must first be trained before it can be used for 3D reconstruction. And training requires images where we already have ground-truth 3D data for each image.

SLAM

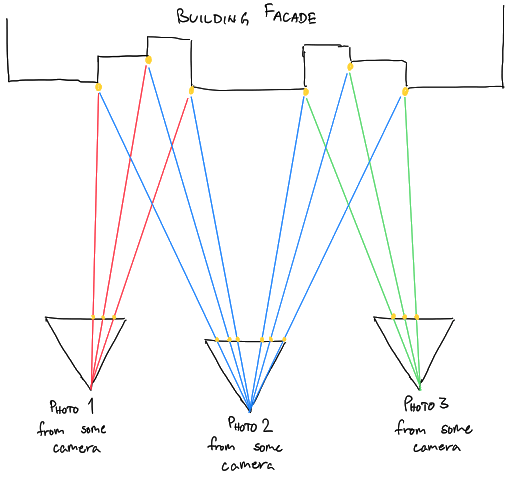

SLAM stands for simultaneous localization and mapping. SLAM is similar to DNNs in that it is also an attempt to perform 3D reconstruction without the use of specialized sensors. It only requires a set of photographs of the scene to reconstruct. However, unlike DNNs, SLAM uses geometry in the form of mathematical models for each of the cameras that captured the photos and the geometric constraints of the physical world.

It starts with a set of photos of the scene to reconstruct as the input. This set can be anywhere from 10s of photos 1000s of photos. SLAM then finds unique points in the scene, where each point appears in at least a few photos. It then solves a set of linear equations (and some nonlinear equations) to figure out the position of those points in the scene as well as the position and orientation of the cameras that must have occurred in order for the points to appear the way they did in each photo.

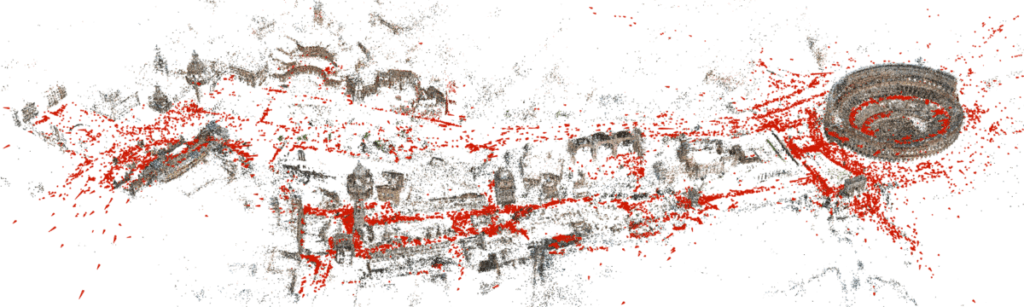

The picture above is a reconstruction of central Rome created by a SLAM software package called COLMAP. You may recognize the Colosseum on the far right. Each of the red dots is actually a little side-ways pyramid to show the position and orientation of a camera that took one photo used in this reconstruction. All the other points that make up the buildings, or parts of buildings, are those unique points that the SLAM algorithm found in multiple photos used for this reconstruction.

Our Starting Point: SLAM

Our goal at RoadBotics is to create a way for governments to easily and scalably produce accurate 3D models of their infrastructure. With that in mind, we have chosen to develop a SLAM-based approach for a number of reasons.

The two biggest reasons are 1) SLAM techniques produce visually recognisable 3D reconstructions and 2) SLAM doesn’t have specialized hardware requirements beyond high-quality image capture, which means that just like with other RoadBotics solutions, a customer only needs a smartphone.

Visual Recognition

To elaborate on the first point, SLAM is capable of producing 3D reconstructions that not only have the 3D structure of the scene, but also the colors of the scene.

Structured light and LiDAR usually only reproduce the 3D structure without any color because they generate their own illumination in the non-visible light spectrum. In theory, color can be added later from pictures taken from a camera mounted nearby, but this reveals a second problem.

Point clouds generated by structured light and LiDAR tend to be on the order of 100s to 100,000s of points. This is a limitation of the hardware since they have to illuminate the scene on their own, point-by-point. SLAM, in contrast, can produce reconstructions in the millions or even tens of millions of points, in part because modern cameras pack millions of pixels. That increase in granularity of detail is critical since visual assessment is a key deliverable.

No Special Sensors

The second point is also important: SLAM can produce high quality reconstructions from images taken by a smartphone camera. The ubiquity of smartphones and the ease of use of their cameras makes SLAM a much better foundation than structured light or LiDAR, which require special hardware and software that would require customer training.

What about DNNs?

Deep neural networks are also capable of these two points: producing high density, colorized reconstructions without the need for special sensors. However, DNNs have their own drawbacks such as the large amount of labeled data required to train a DNN and the black-box nature of neural networks which can make diagnosing errors more difficult.

RoadBotics is not the only company to see potential in SLAM-based 3D reconstruction. There are a number of open-source software packages that implement various SLAM techniques: VisualSFM, OrbSLAM, VinsMONO, OpenMVG, COLMAP, and more. However, these packages tend to work very well under a set of assumptions that have evolved in tandem with the typical use cases for the software, like the examples we discussed earlier in our earlier blog post. These assumptions include that you are capturing an object or a single scene (as opposed to a very long continuous asset, like a sidewalk); that you are willing to accept defects or able to manually correct them after making the reconstruction; and that you’re building a single reconstruction (like the COLMAP reconstruction of central Rome shown above) rather than building many in a scalable process and stitching them together.

None of these assumptions are true for RoadBotics; we emphasize automated, highly-scalable solutions because they are cost-efficient and necessary for our clients with assets at their scale. So while these software packages are useful to us, they don’t get us very far in producing the kinds of reconstructions that will help our clients.

Creating city-scale 3D reconstructions of infrastructure, like roads or sidewalks, that are accurate enough for visual inspection thus require developing novel solutions to a number of problems. Some of them – as mentioned above – requires creating new software that will produce, store, and display these very large reconstructions. But there are also unsolved research problems in capturing assets of this sort that have mostly remained unaddressed till now, that we will talk about in our next blog post. These problems are the focus of our work, and solving them will enable a revolution in infrastructure inspection and maintenance.

3D reconstructions at scale are a big step to automating things like sidewalk measurements for ADA compliance to help make sure a city’s resources serve all of their constituents effectively and efficiently.

Stay tuned as we dive deeper into these issues and reveal sneak peeks into how we’re solving them!