So far in our 3-D reconstruction series, we’ve covered an introduction to 3D reconstruction, how to create one, and part 1 of the SLAM methodology.

Next, we’re going to show you the last of the major obstacles the R&D team has been tackling to make SLAM methods work at RoadBotics. As a bonus, you’ll learn a bit about how modern smartphone cameras work!

Rolling Shutter

An intriguing problem that spans almost all of modern digital image and video capture is the rolling shutter problem. It is relatively simple to describe, but a bit of background about how cameras work is helpful.

Before the age of ubiquitous digital cameras, analog film cameras captured images by exposing a photosensitive material (the film) to light. Incidentally, this is why analog film requires a dark room to be developed since the medium itself is sensitive to light. The inside of the camera where the film is loaded protects the film from light via a device called a shutter. When the button to take a picture is pressed, the shutter, which is initially shut to block light, opens briefly to expose the film inside the camera to the light coming in through the lens of the camera, and then shuts again. The mechanism of the shutter opening and closing rapidly is what makes the distinctive “taking a photograph” sound of a handheld camera, and the sound most often used with digital cameras to indicate a photo is being taken. This method of capturing the light in a scene is effectively uniform and instantaneous across the film, which is why this type of shutter is often referred to as a global shutter, in the sense of “global” as “complete.”

Most digital cameras do not work the same way. Modern image capture devices (i.e., cameras on our smartphones) are based on integrated semiconductor chips called CMOS sensors. These CMOS-based sensors replace traditional film with a grid of pixels, capturing the light that hits each pixel in a row-by-row manner. This is called a rolling shutter, as opposed to the global shutter.

The following animation shows the difference. The timing in the rolling shutter animation is exaggerated for effect, but the capture delay between individual rows is a real consequence of this technology.

Though it only has a simple difference in operation, a rolling shutter turns out to have many profound side-effects in digital image capture when either the camera is moving (as with dashboard collection) or objects in the frame are moving. This is appropriately called the rolling shutter effect.

This effect is noticed when objects in the frame, or the camera itself, are moving at a speed comparable to the speed of the rolling shutter because the tiny delay between capturing each row means that a slightly different scene is being captured by each row due to the capture not being simultaneous.

The following animation illustrates the problem:

The above animation may seem dramatic, but below is a real-life image of a spinning aircraft propeller that exhibits the same dramatic warping:

Unfortunately for us, and for anyone using a smartphone camera, the rolling shutter effect is not limited to such obvious circumstances. The effect can be more subtle and difficult to notice.

For instance, you can notice warping in some parts of the following image, but without forewarning, you could easily assume this fence was just bent in parts. Even after we’ve told you this, you may still find it difficult to visually acknowledge that this image does not accurately capture the scene.

Why Do Cameras Have Rolling Shutters?

So if analog cameras use global shutters and rolling shutters produce warped images, why use them?

They are much more efficient than global shutters. We can see their advantage with some simple math.

Many smartphones (including the ones we use for data collection at RoadBotics) collect HD video at 30 frames per second. That’s 30 images that each have 2,073,600 pixels at 24 bits per pixel every second.

(30 frames x 2,073,600 pixels x 24 bits) / (8 bits per byte) = 186,624,000 bytes per second

Or about 180 megabytes per second. That’s a literal firehose of data!

Every frame is about 6 megabytes, and if your smartphone had a global shutter, it would have to record that 6 megabytes instantaneously between frame exposures. With a rolling shutter, your smartphone still has to record that firehose of data, but it can record it row-by-row, moving the data from one row of pixels into memory while the other rows are being exposed to light. This trade-off dramatically reduces the cost of the camera in your smartphone while introducing some warping that humans don’t really notice when playing back the video at 30 fps. It’s only when we pull individual frames out of the video and look at them for a second or longer that we notice the warp.

How Rolling Shutter Effects 3D Reconstructions

This warping ends up having drastic consequences for reconstruction, given that 1) the effect is stronger the faster the relative motion between the camera and the scene (RoadBotics collects data at road speeds that can be quite fast), and 2) we routinely collect rapidly changing background imagery (for example, trees and buildings).

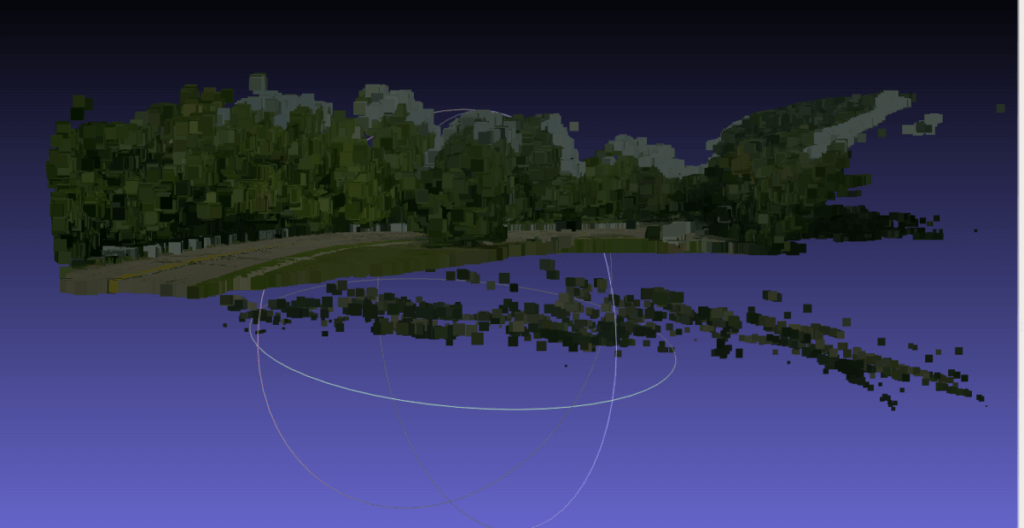

As an example, consider the following angled view of one of the reconstructions we looked at in our last blog post:

The top part of the reconstruction looks normal, but there are a lot of points that seem to be beneath the ground!

None of the images being fed into the reconstruction had subterranean data, so how and why would a reconstruction process produce this?

The answer is that the input images were collected using a smartphone mounted as a dashcam, creating many instances of rolling shutter artefacts as the car traveled down the road.

Even though many of these are hard or practically impossible for humans to notice in a picture (occurring in the foliage, in the clouds, on the road surface), the computer, which uses the precise pixel location of features to determine their location in 3D space, takes all of them into account. While localizing the warped features, the algorithm tries to reconcile the apparent position differences and then incorrectly determines that those parts of the scene are located in places that don’t make sense (such as below the surface of the road) in order to make them fit the warped images.

Readers of our previous post might ask, can RANSAC handle excluding these anomalies? Unfortunately, the warped features created by a rolling shutter can be subtle enough that they still mathematically fit into the remaining scene (which is what RANSAC considers as “good enough to keep”), even though we can visually see that they do not fit.

The rolling shutter problem is an open problem in computer vision. There are two general approaches to solve the problem.

One is a preprocessing correction: train a neural network to recognize the distortions in the input data and correct them before the data is used for reconstruction. There is a lot of ongoing research in this domain (for an example, see http://cseweb.ucsd.edu/~mkchandraker/pdf/cvpr19_rollingshutter.pdf which was a paper presented at CVPR, one of the most prestigious academic conferences in computer vision), and some of the latest results are adaptable to our needs.

The second is a post-processing correction: automatically recognize rolling shutter distortions after the fact and then automatically excise them from the reconstruction. RoadBotics’s reconstructions are generally aimed at civil infrastructure (roads, sidewalks, etc.), and these generally are planar assets. (You should be very worried about roads that do not fit a planar surface! It usually means something like this has happened.) Therefore, we can use standard curve-fitting techniques on the raw 3D data in the reconstruction and then use statistical heuristics to cut out data that lies below the plane or otherwise is implausibly far away from the surfaces we care about.

For an optimal result, we’ve found that it’s good to use both approaches. The preprocessing step tends to improve the overall accuracy of the reconstruction, and the post-processing step simplifies the reconstruction to focus on what we really care about.

Stay tuned for our final blog post about reconstruction, which will showcase some of our most impressive results so far!