Up until this point in our R&D series, we’ve focused on the techniques for creating high-quality 3D reconstructions. While we still wrestle with the challenges we discussed in previous posts, let’s dive into the technical details of one of the cool things we can do once we have a good reconstruction of a street. Let’s dive into locationization of objects in the scene.

Street signs are an important city asset, helping to coordinate drivers, pedestrians, and others on the street. Their standard shapes, sizes, and colors help people (and even computers) easily find them in visually complex scenes.

The latest machine learning algorithms are quite adept at finding street signs in an image and, by providing a consistent pattern across multiple images, street signs are even helpful as anchor points for the SLAM techniques we use to create 3D reconstructions.

However, this uniformity has some drawbacks. Simply identifying a street sign in an image, even when the image has a GPS stamp, doesn’t tell you the location of the street sign in the real world.

As an example, take the image above. Knowing the GPS coordinates of the camera when this photo was taken is useful (though not exact) for stamping the location of the street signs attached to the traffic light pole. But for the street sign in the bottom left corner, this photo is too far away for it to be a good proxy. Other photos of that street sign that are closer to it will certainly be better proxies for the GPS location of the sign, but how can we know that the speed limit sign in those photos is the same one we see here? All 30-mph speed limit signs in any single city tend to look the same.

The GPS locations of the photos in question can help disambiguate if two photos are looking at the same street sign, but there are plenty of cases where two street signs are so close together that GPS alone is not accurate enough (see the example in the photo above).

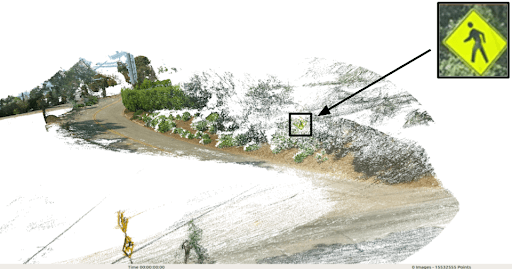

However, if we have a 3D reconstruction of a street, we can pin-point the location of each sign in the reconstruction relative to the position and orientation of the camera for each photo used in the reconstruction. Let’s show an example.

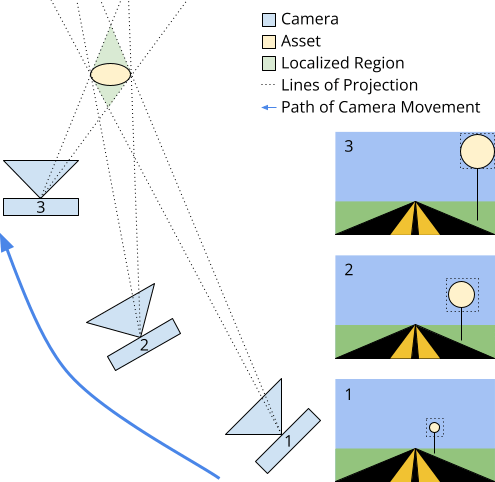

In the series below, we see several photos of a pedestrian crossing street sign, one that is getting closer as the car in which the camera is mounted makes a turn.

If you look very closely, you can even see a bounding box around the sign in each photo. This is the automatic street sign detection performed by a deep learning algorithm. Although it may be obvious to us, it is not trivial for a computer to say that all of these photos are of the exact same street sign.

So, we create a 3D reconstruction using these photos, along with the ones before and after, too. Now with only one street sign in the reconstruction, we can be certain that the signs identified above all are indeed the same one.

On top of that, we also now know the location of the street sign with respect to the positions and orientations of the camera in each photo. Using this information and the GPS coordinates of the camera in each photo, we can calculate the location of the sign with much higher accuracy than simply assigning it the location of one of the photos.

Now, what happens if the 3D reconstruction produced by SLAM doesn’t contain the street sign (or some other asset) that we want to locate? Modern SLAM still relies on some amount of random point selection in each photo, and there is a not-insignificant chance that the asset of interest doesn’t end up in the final reconstruction.

Even in this case, as long as we can mark the asset of interest with a bounding box in a few photos used for the reconstruction, we can project those bounding boxes out into 3D space (as a rectangular 3D box, kind of like a french fry that expands in width as it extends away from the camera) and use the intersection of those boxes as an approximate location for the asset of interest.

To help visualize this, see the photo on the left. From a top-down view, imagine a camera moving along the path of the blue arrow.

Using a 3D reconstruction, we can determine the location and orientation of the camera at a few different points in time. Then, in the photograph taken at each of these locations, we can draw a bounding box around the asset (the yellow circle) we want to locate in 3D space. We then project that bounding box out of the photo, into the 3D world along the lines of projection, and use the intersection of these projections to find an approximate location for the asset in the 3D world. The localization region will almost certainly be larger than the asset itself, but it still serves as a better location marker than simply using the location of one of the cameras that captured the asset.

As always, stay tuned for the next post in our Research and Development blog series!